From: David Spring, Director

Washington Environmental Protection Coalition

49006 SE 115th Street North Bend WA 98045

Email:

Cell: (425) 876-9149

To: Greg Wahl, Project Lead,

USDA-Forest Service, Olympic National Forest

1835 Black Lake Blvd SW Olympia, WA 98512

Email:

RE: Pacific Northwest Electronic Warfare Range Special Use Permit Application

and Environmental Assessment #42759

TRANSMITTED TO https://cara.ecosystem-management.org/Public//CommentInput?Project=42759

Dear Mr. Wahl,

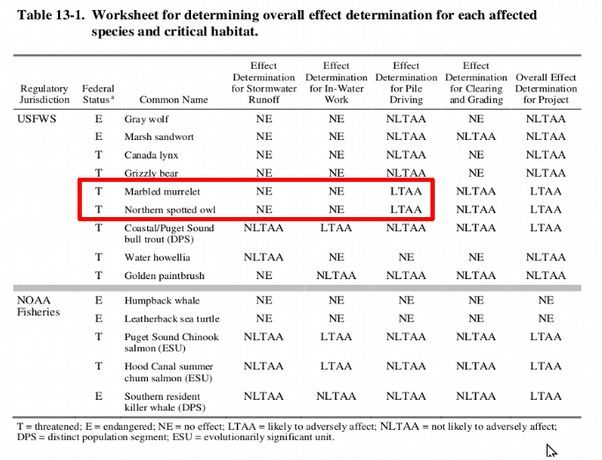

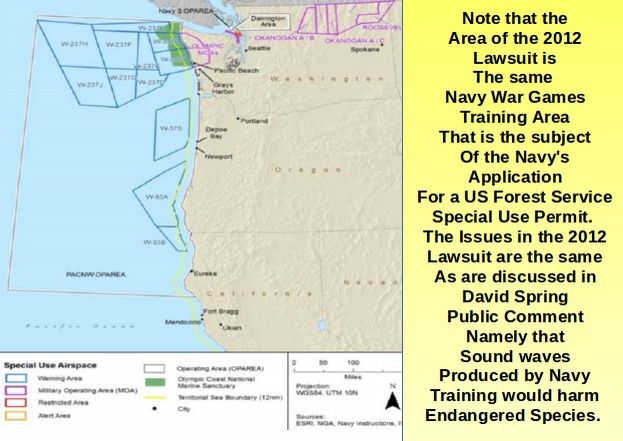

For the record, this is my public comment regarding the US Navy's application for a Special Use Permit to expand their use of US Forest Service lands beginning in 2015. As described in the Navy's Environmental Assessment, submitted in September 2014, the US Navy's proposed expansion includes allowing three “mobile electromagnetic radiation emitters” to be moved around between 12 different locations on US Forest Service land (and 3 locations on Washington State Department of Natural Resources land) where the mobile transmitters will “interact” with up to 135 “US Navy F18 Growler military jets” for 12 to 16 hours per day for 260 days per year for the next 10 to 20 years. The Forest Service land that the US Navy is requesting a Special Use Permit to use is on or near Critical Habitat for endangered species, included the Northern Spotted Owls and Marbled Murrelets. The US Navy claims in their Environmental Assessment that these electronic warfare games, which would include more than 22,000 “fly overs” of critical habitat for these endangered species per year, “may affect, but would not adversely affect” these endangered species. However, because the US Forest Service is under a binding 1994 Record of Decision (1994 ROD) to affirmatively protect these endangered species and their critical habitat, the US Forest Service is required to independently and accurately determine whether granting a Special Use Permit to the US Navy would harm these endangered species or their habitat.

Among the Navy's claims in their 2014 Environmental Assessment are the following:

1. Northern Spotted Owls would not be disturbed by a noise level of 92 decibels. This claim is based entirely on a misrepresentation of a study of Mexican spotted owls.

2. The noise emitted by Navy F18 Growler military jets would not exceed 89 decibels. This claim was extrapolated from a measurement nearly 5 miles away from the jets.

3. The F18 Growler jets would be at least 1200 feet above the surface of critical habitat.

4. The F18 Growler jets would not exceed the maximum adverse sound level of 92 decibels for more than one second.

5. In 2010, the US Fish and Wildlife Service issued a Biological Opinion finding that fly overs of the F18 Growler “may affect, but would not adversely affect” Northern Spotted Owls, Marbled Murrelets and their critical habitat based on the above 4 claims.

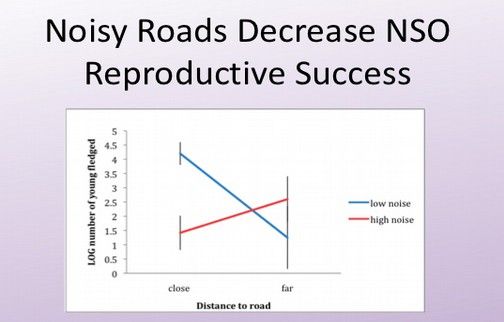

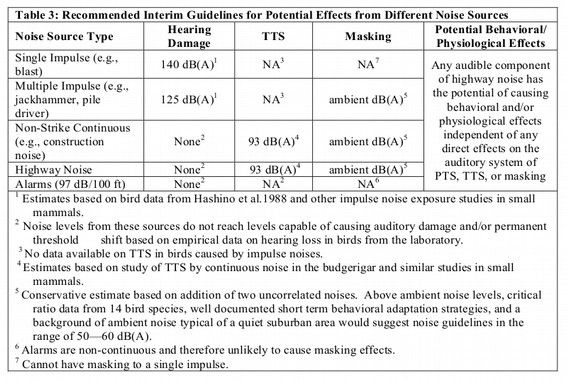

In this public comment, I will provide substantial scientific evidence that the Navy's claims are not accurate. First, we will show that, according to US Fish and Wildlife Service written policies, northern spotted owls may be adversely affected by noise as low as 60 decibels.

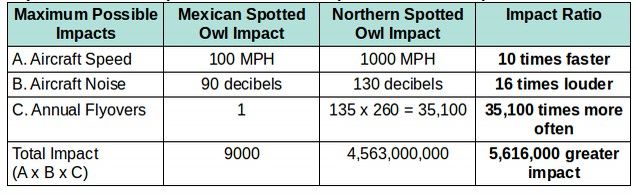

Northern spotted owls have specifically evolved for adaptation to the extremely quiet environment of an Old Growth Forest with a background noise level as low as 10 decibels. Such sensitive hearing cannot be reconciled with the Mexican Spotted Owl study. Nor are the conditions proposed by the Navy for the Olympic Electronic Warfare Range similar to the Mexican Spotted Owl study. In the Mexican Spotted Owl study (Delaney, D. K., T. G. Grubb, P. Beier, L. L. Pater, and M. H. Reiser. 1999. Effects of helicopter noise on Mexican Spotted Owls. J. Wildl. Manage. 63:60-76), helicopters approached the owls gradually at a speed of less than 80 miles per hour. By comparison, the Navy proposes to have military jets approach Northern Spotted Owls at speeds of greater than 1000 miles per hour. The maximum noise level of a single helicopter was only 90 dB while the maximum noise level of three or more Navy jets is 130 dB – which is 16 times louder than 90 dB. Finally, the authors of the Mexican study allowed an average of 13 days between tests to avoid chronic exposure of the owls – while the Navy is proposing to subject owls to noise bombardments up to 11 times a day, 5 days a week for 52 weeks in a row for 260 days per year for the next 10 to 20 years. It is not appropriate for the US Navy to use a single and radically different study of the effect of helicopters on Mexican spotted owls to make assumptions regarding the effect of Growler jets with speeds ten times higher and noise levels 16 times greater – to make conclusions about adverse affects on Northern Spotted Owls.

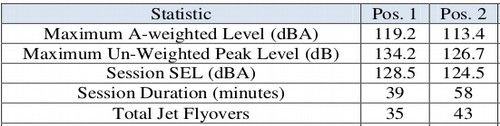

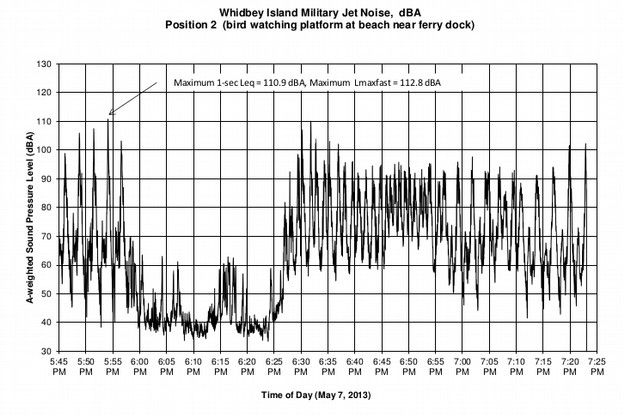

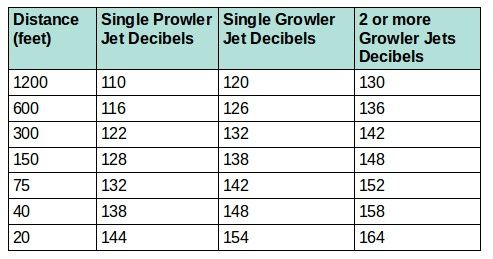

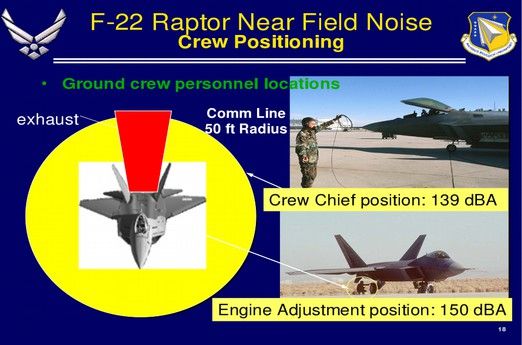

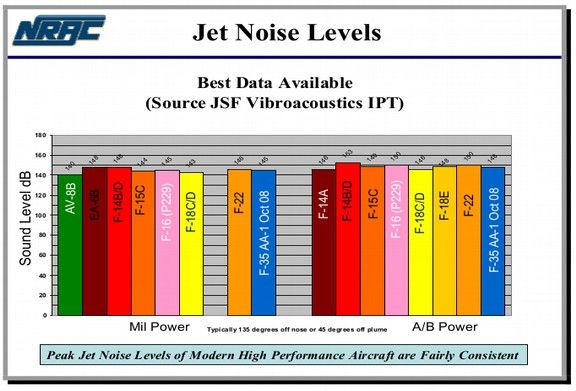

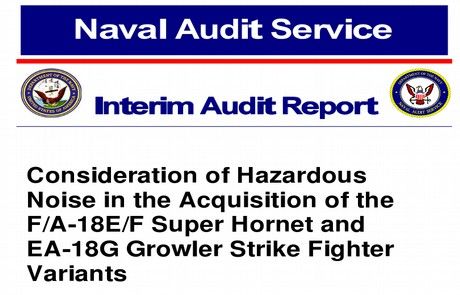

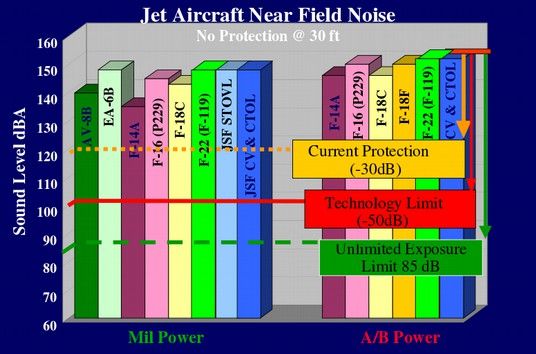

Second, we will provide substantial scientific evidence that the F18 Growler military jets are much louder that the “Prowler” jets they are replacing. According to a 2008 US Navy Auditor report, the F18 Growler military jets emit noise up to 150 decibels (which equals 130 decibels at 1200 feet). This toxic noise level was confirmed in a private independent study in 2012. The Navy is well aware of the toxic noise problem of the F18 Growler jets and yet elected to deliberately provide misleading information to the US Fish and Wildlife Service about the noise levels of F18 Growler jets in 2010. Combined with 10 times faster aircraft speed and 64 times louder maximum noise level means that the Northern Spotted Owls would be subject to an impact that was 5.6 million times greater than the impact Mexican Spotted Owls were subjected to in the 1996 study used by the Navy to justify their proposed project.

Impact on Mexican Spotted Owls versus Impact on Northern Spotted Owls

Third, we will show that spotted owls nest in Old Growth trees which extend more than 200 feet above the ground. Therefore, the Navy's proposed standard of flying 1200 feet above the ground would result in F18 Growler jets flying as close as 1000 feet above spotted owls during their military flyovers of the three mobile transmitters should the US Forest Service grant a Special Use Permit to allow the mobile transmitters on land which has been designated as critical habitat for spotted owls. This would expose spotted owls to noise levels over 120 decibels and possibly as high as 140 decibels.

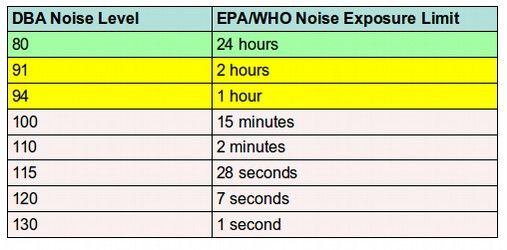

Fourth, whether using the “60 decibel standard” recommended by the US Fish and Wildlife Service or the “90 decibel standard” recommended by the US Navy, we will show that the F18 Growler fly overs would exceed harmful noise levels for much more than one second and likely as long as 60 seconds.

Fifth, we will show that the US Fish and Wildlife Service failed to independently and accurately verify the claims made by the US Navy when they issued their 2010 Biological Opinion. Instead, the US Fish and Wildlife Service merely assumed that the claims made by the Navy were accurate. The US Fish and Wildlife Service accepted the US Navy's absurd claim that a study of the effect of a single slow moving and relatively quiet helicopter on Mexican Spotted owls could be used to predict the effect of several fast moving and extremely loud military jets would have on Northern Spotted Owls.

It is disturbing that the Navy knowingly submitted misleading information to the US Forest Service regarding the loudness of the F18 Growler jets. And it is even more disturbing that the US Fish and Wildlife Service apparently did not even bother to read the Mexican Owl Study – where they would have learned that helicopters move much more slowly than military jets. However, what is most disturbing is that the US Fish and Wildlife Service failed to make an independent and accurate assessment of the claims made by the Navy. This failure to perform a required duty by the US Fish and Wildlife Service was a clear violation of the Endangered Species Act and a serious violation of the 1994 Record of Decision. Had the US Fish and Wildlife Service conducted an independent investigation, they would have found that the noise levels of F18 Growler fly overs would not only adversely affect the spotted owls, but would greatly accelerate the rate of extinction of spotted owls.

Burden of Proof is on the US Navy

Under the Endangered Species Act and the 1994 Record of Decision, it is up to the US Navy to answer questions and provide information confirming that their proposed actions described in their application for a Forest Service Special Use Permit would not adversely affect the viability of the spotted owl population on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains. The Navy has thus far failed to provide the needed information.

This concludes the Executive Summary to my Public Comments. The following page is a Table of Contents for the remaining 14 sections of this Public Comment.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 4

David Spring November 28 2014 Public Comments

Table of Contents

Part 1... Four Essential Unanswered Questions........................................ Page 5

Part 2... Request for Immediate Actions..................................................... Page 7

Part 3... Using Decibels to Determine Impact of Jets on Owls................. Page 8

Part 4... Laws and Studies of Spotted Owl Populations........................... Page 13

Part 5... Evidence Spotted Owls are Near the Extinction Threshold....... Page 29

Part 6... Understanding the Extremely Quiet World of Spotted Owls...... Page 30

Part 7... The Effect of Toxic Noise on Spotted Owls.................................. Page 35

Part 8... Calculating the Level of Growler Jet Noise.................................. Page 42

Part 9... Evidence that Toxic Growler Jet Noise will Harm Spotted Owls Page 47

Part 10... How the US Navy misled US Fish and Wildlife Service

to Conclude that Noise from Growler Jets was Below 90 decibels......... Page 50

Part 11... Why the Navy mislead the US Fish and Wildlife Service

about the noise levels of its new F18 Growler jets.................................... Page 56

Part 12... Legal Action Against the US Navy Warfare Expansion Plans Page 58

Part 13... 2013 Federal Court Ruling Finding Navy Plan

Violates the Endangered Species Act......................................................... Page 61

Part 14... Summary and Conclusions.......................................................... Page 69

List of Appendices (submitted electronically as separate attachments)

Appendix A: 1996 David Spring Study of Spotted Owl Populations

Appendix B: 2003 David Spring Study of Spotted Owl Populations

Appendix C: 2013 JGL Acoustics Report on Whidbey Island Military Jet Noise

Appendix D: 2012 Earth Justice Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief

Appendix E: 2013 Federal Court Ruling in favor of Earth Justice

and Finding that the US Navy Warfare Expansion Plan Violates the ESA

David Spring Public Comment, Page 5

Part 1... Four Essential Unanswered Questions

Among many unanswered objective questions are the following:

1. What are maximum and average decibel readings of F18 Growler jets at flyover elevations of 900 feet, 1200 feet, 2000 feet and 6,000 feet above the ground?

Given that decibels are on a logarithmic and not a linear scale, it is not acceptable or reasonable for the Navy to only provide decibel readings at a distance of 4 miles (21,000 feet) as they did in their 2010 report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service and then make inaccurate and unfounded claims about how such a reading at 21,000 feet might be translated to an estimated reading of 1200 feet. The Navy must conduct scientifically rigorous tests with independent monitors and then provide the public, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Forest Service with accurate information before any determination is made regarding a Special Use Permit.

2. What are maximum and average decibel readings of older Prowler jets at elevations of 900 feet, 1200 feet, 2000 feet and 6,000 feet above the ground?

The Navy has claimed that the new Growler jets are actually quieter than the older Prowler jets. This claim is directly contradicted by a 2008 Report from their own Navy Auditor as well as a 2012 independent study as well as thousands of reports and videos by private citizens all of which indicate that the Growler jets are about twice as noisy as the Prowler jets (or about 10 decibels louder than the older Prowler jets.). Given that one of the factors to be evaluated is historical use, it is essential that the public, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Forest Service have a clear objective understanding of what the historical baseline noise levels might have been. The Navy still has lots of Prowler jets and they should be required to complete a Noise Study of these Prowler jets with independent monitors and then provide the public, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Forest Service with accurate information before any determination is made regarding a Special Use Permit.

3. What is the current population of spotted owls on the Western slopes of the Olympic Mountains, what is their rate of decline and what is the extinction threshold for this population?

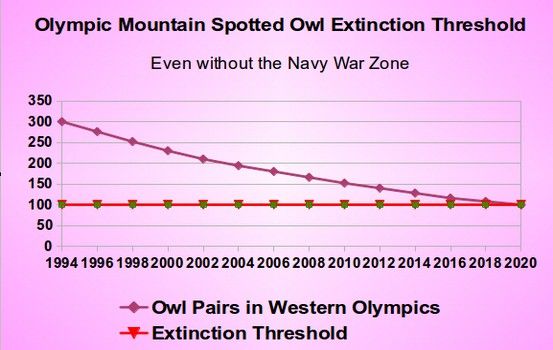

The 1994 Record of Decision and the Endangered Species Act require the US Forest Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to affirmatively monitor the spotted owl population. The latest information by Forsman in 2012 indicates that there may be as few as 300 pairs of spotted owls remaining in the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains and that their rate of decline is about 4% per year (a loss of 12 pairs of spotted owls per year). My own analysis based on the work of biologist E. O. Wilson is that 300 pairs of spotted owls is already very near the extinction threshold and thus the loss of even a single pair of spotted owls may place the entire population of spotted owls in the Olympic Mountains at the brink of extinction.

4. What is the maximum noise volume that Northern Spotted Owls can endure before being disturbed?

I have personally led more than 3,000 outings to Old Growth forests during the past 40 years. I have personally witnessed on many occasions northern spotted owls disturbed by normal human conversation of my students - which was only 60 decibels.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 6

I have also personally observed on many occasions that northern spotted owls are not disturbed by human whispers (which are only 30 decibels. I am therefore convinced that the threshold for disturbing Northern Spotted Owls is somewhere between 40 to 60 decibels.

Based on over 40 years of personal experience with spotted owls in spotted owl habitat, I strongly disagrees with the US Navy claim that spotted owls would not be disturbed by a noise level of 90 decibels. Even humans suffer permanent hearing damage at chronic exposure to 90 decibels and our ears are no where near as sensitive to sound as spotted owl ears. Instead, I support the US Fish and Wildlife Field Survey Policy of avoiding any noise above 50 decibels (including human conversations of 60 decibels) when conducting surveys in spotted owl habitat. I instruct my students to whisper (which is only 30 decibels) when in spotted owl habitat. The US Fish and Wildlife Service also instructs their employees to whisper. My personal experience based upon more than 40 years of observing spotted owls is that an absolute upper limit of 60 decibels is the correct standard for spotted owl habitat. This low noise threshold is important not only for spotted owl nesting. It is also important for spotted owl hunting. The owls use their ears to hunt. If owls are inflicted with permanent hearing damage, which would be the case for anything over 80 decibels, they would not be able to hunt and the entire population would soon go extinct.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service must conduct a Noise Assessment of Northern Spotted Owl behavior to objectively determine the maximum noise level they can tolerate. This study can be completed in 60 days and can be conducted at the same time that they are doing the survey of the spotted owl population. They will need accurate sound emission tools for the study to be scientifically valid and reliable. I propose that the US Navy be required to provide the US Fish and Wildlife Service with recordings of F18 Growler jets fly overs at 40 decibels, 50 decibels, 60 decibels, 70 decibels, 80 decibels and 90 decibels. The Navy must disclose how far away (what elevation the jet was flying at) in feet when each recording was made in order to achieve these decibel readings. The Fish and Wildlife Service can then locate nesting owls and start the lowest recording of 40 decibels. Each recording should last for at least 10 seconds but no more than 20 seconds and should be stopped if the owls are disturbed. If the owls are not bothered by the 40 decibel tape, after a five minute pause, the 50 decibel tape should be started. Only if the owl is not disturbed, the test can continue all the way up to 90 decibels. The test should be conducted on at least 10 owls to have a valid sample size and a maximum of 20 owls to avoid harm to the species. If the Navy is correct, then no owls would be disturbed by this test. If I am correct, then at least half of the owls would be disturbed by the time the recording reaches 60 decibels and all of the owls would be disturbed by the time the recording reaches 80 decibels.

The study should be completed by May 1 2015 so that the public would have an opportunity to read it before the Public Hearings start on May 15 2015. I realize that due to severe budget cuts, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and/or the US Forest Service may not have the funds or staff needed to conduct such a study of spotted owl populations and noise responses.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 7

However, because the Navy is the one who has proposed this expansion of use and is asking for a Special Use Permit to allow them to use critical habitat in this manner, it is up to the US Navy to pay for such a study. In the absence of such a study, the studies by Forsman and others including my own studies must stand as the “best available scientific evidence” on spotted owl populations and behaviors and the application for a Special Use Permit must be denied.

Part 2... Request for Immediate Actions

Based on the information and evidence provided in this public comment report, and based on the failure of the US Navy to supply essential information need to confirm that their proposed actions will not adversely impact the survival of endangered species in the Olympic Mountains, I ask the US Forest to take the following immediate actions:

1. Require the US Navy to conduct Noise studies of the F18 Growler jets and older Prowler jets and provide this information to the Forest Service and to the public no later than May 1 2015.

2. Require the US Navy to pay either the US Forest Service or US Fish and Wildlife Service to conduct a field survey of the spotted owl population on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains and determine the rate of population decline and estimate the extinction threshold for this population. This study should also be completed no later than May 1 2015.

3. Extend the public comment period until July 1 2015. This will give the US Navy time to conduct the needed Noise studies of the F18 Growler jets and the older Prowler jets. It will also give the US Fish and Wildlife Service time to complete a survey of spotted owls on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains and submit their report to the public by May 1 2015.

4. Conduct official and recorded public hearings in all affected communities as required by NEPA between May 15 2015 and June 15 2015 to allow the public a reasonable opportunity to ask questions of US Forest Service and US Navy officials and to make public comments on the proposed application. Reasonable opportunity means that each member of the public should be allowed at least 3 minutes to ask their questions and make their comments. This would also 20 people per hour to ask questions. Thus, to allow 200 people in each community to ask questions, the entire hearing should be scheduled for at least 10 hours and should be held in a room which would allow the attendance of at least 200 members of the public to sit.

5. Request that the Navy suspend all war game operations over the Olympic Peninsula until an accurate determination can be made regarding the effect that these current war games might have on the survivability of the spotted owl population in the Olympic Mountains. The evidence provided in this report, which includes the best available science on spotted owl populations indicates that even the current actions of the Navy are in violation of the Endangered Species Act and the 1994 Record of Decision. It is essential that these operations be halted immediately in order to protect the spotted owls on the Olympic Peninsula from going over the extinction threshold.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 8

The following public comments are a detailed explanation of why these actions are needed and are required by law.

Part 3... Using Decibels to Objectively Determine Impact of Jet Noise on Owls

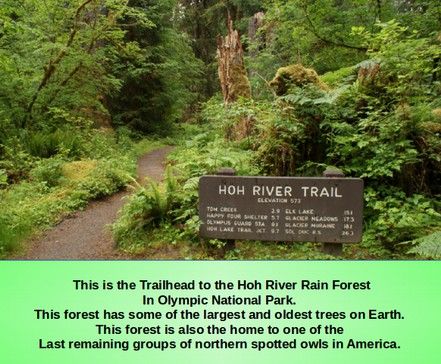

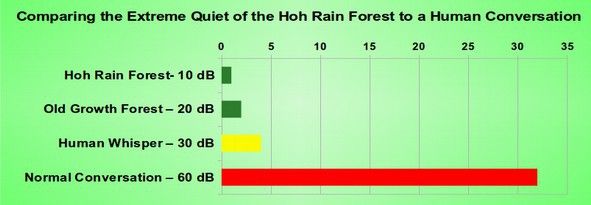

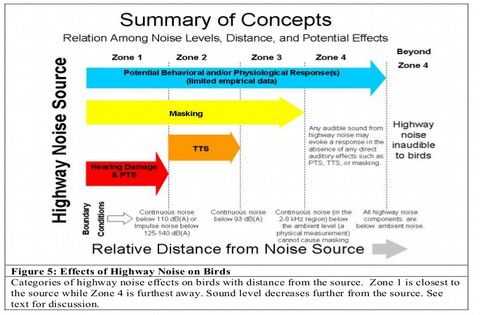

Because decibels are used to measure sound and because it is not a linear scale, we will begin with a brief introduction to the topic of decibels. Decibels range on a scale from 0 to 200 with zero being the quietest sound that any human can hear and 200 being a blast so loud as to cause instant permanent deafness. Most humans have been so conditioned to live in a noisy world that they actually cannot hear sounds below about 20 decibels – which is the average sound level in an Old Growth forest. The Hoh Rain Forest in Olympic National Park has been recorded to only be 10 decibels. (see the One Square Inch Project for more information on this). http://onesquareinch.org/

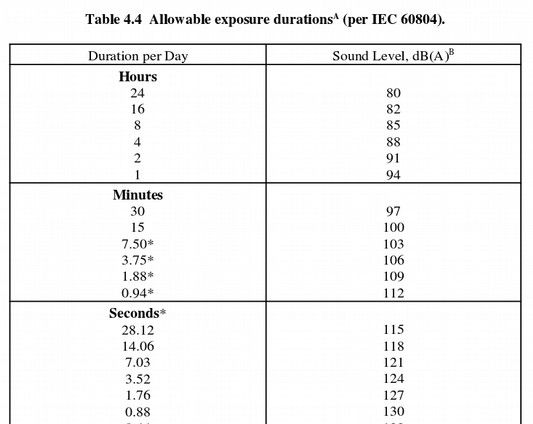

Unfiltered Decibels versus A Scale Decibels

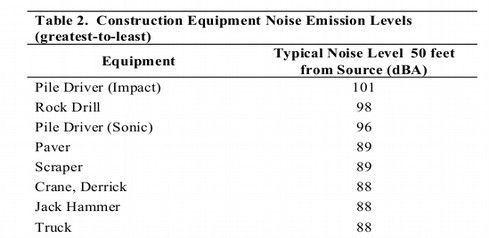

There are a couple of different ways to measure decibels. Both use decibel meters. The first way is to capture sound across all frequencies. Since humans cannot hear all frequencies, we are mainly interested in sound that humans can hear. Therefore nearly all commonly available decibel meters screen out very high and very low frequencies and measure only the middle sound frequencies. When the high and low frequencies are eliminated the remaining frequencies – audible to humans – is called the A scale. Technically, sound measured with such an A scale sound meter is indicated as dBA. For example 20 dBA is the sound level of a typical Old Growth forest. However, since nearly all sound meters are A scale meters, in this report when we use the term “decibel” we are referring to decibels measured on the A scale with an A scale sound meter. We will also use the abbreviated notation dB to mean dBA. When we say that the sound level in an Old Growth forest is 20 dB – what we really mean is that it is 20 dBA and was measured by a common A Scale sound meter or other related human benchmark.

Logarithmic versus Linear Sound Scales

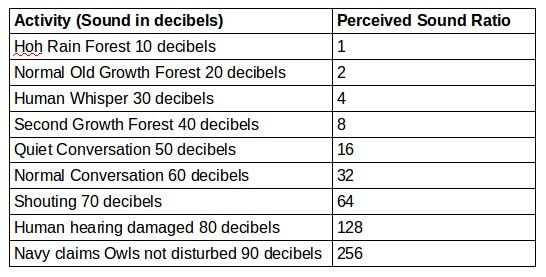

The quietest recorded sound is about 10 decibels. It was recorded in the Hoh Rain Forest. Each 10 decibel increase means that humans and wildlife would perceived the sound to have doubled. This does not mean the sound's absolute pressure actually doubled. In fact, the absolute pressure may have increased by a factor of ten. But all sound is processed by the human brain or an animal brain and it is the brain's perception of sound that matters – not the actual pressure of the sound waves. Thus, a sound of 20 decibels is perceived to be about twice as loud as a sound of 10 decibels and a sound of 30 decibels is perceived to be twice as loud as a sound of 20 decibels. Because this way of measuring sound can be confusing to most people, I have created a series of visual tables and graphs.

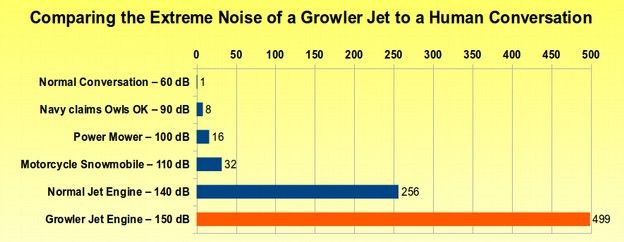

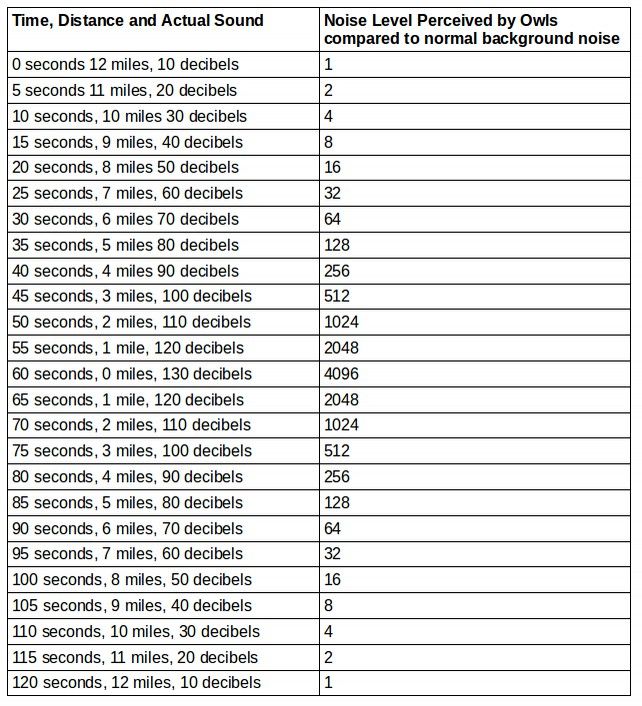

This first table and graph uses a scale of 1 for 10 decibels, 2 for 20 decibels, 4 for 30 decibels, 8 for 40 decibels, 16 for 50 decibels, 32 for 60 decibels, 64 for 70 decibels and 128 for 80 decibels. Since 10 decibels is the sound of the Hoh Rain Forest, this graph can be thought of as how much louder various activities are compared to the extreme quiet of the Hoh Rain Forest.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 9

Comparing the Extremely Quiet World of the Hoh Rain Forest to Human Activities

Here is a graph of the above table.

The above graph makes it easier to compare the extremely quiet world of the Hoh Rain Forest and normal Old Growth Forests that spotted owls have adapted to over millions of years to the Navy's claim that spotted owls are not disturbed by chronic exposure to the toxic noise level of 90 decibels – which is 256 times louder than the Hoh Rain forest!

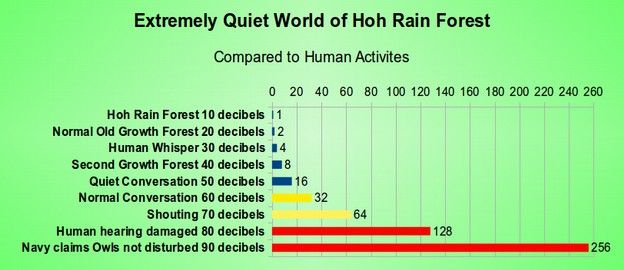

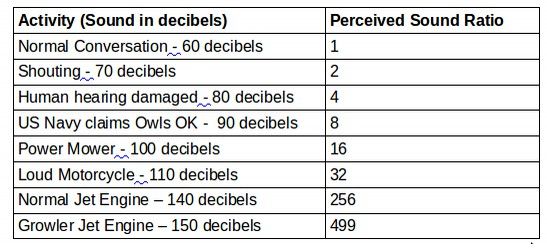

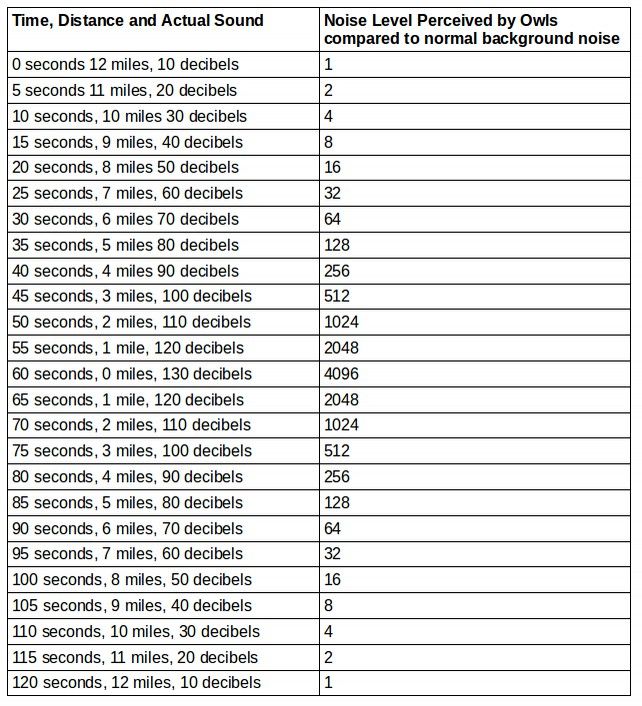

As loud as 90 decibels is, it is nothing compared to the noise level of 150 decibels created by an F18 Growler military jet. To even begin to understand how loud 150 decibels is, I have made the following table and graph with a normal human conversation of 60 decibels set for 1, human shouting of 70 decibels set for 2, human hearing damage level of 80 decibels set for 4, the Navy claim of Growler jet noise level of 90 decibels set for 8, a power mower set for 100 decibels, a loud motorcycle set for 110 decibels, normal jet noise set for 140 decibels and the Growler's actual maximum noise level set for 150 decibels.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 10

Comparing the Extreme Noise of a Growler Military Jet to a Human Conversation

Here is the graph of the above table.

A Growler Jet Engine is 500 times louder than a normal human conversation – and a normal human conversation is known to disturb spotted owls. Since a normal human conversation is 32 times louder than the normal background noise in the Hoh Rain Forest, this means that a growler jet flying over the Hoh Rain forest and within 1000 feet of spotted owls is 16,000 times louder than spotted owls have evolved to hear.

The Navy proposes having four to eight of these Growler jets flying over spotted owls about once or more per hour about 11 times per day with at least 100 fly overs per day for 260 days per year – over 26,000 fly overs per year for the next 10 to 20 years.

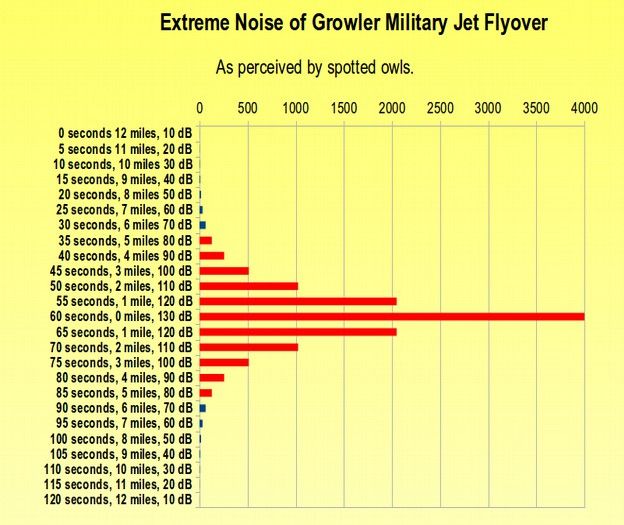

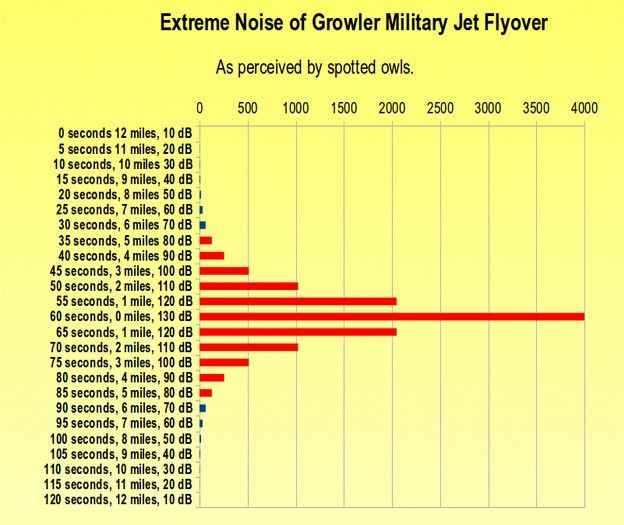

These extremely loud military jets would approach the defenseless owls without any warning beginning before dawn and at a speed of 700 to 1200 miles per hour. 720 miles per hour is 12 miles every minute or 1 mile every five seconds. The owl hearing is so sensitive, that they would likely first hear the Growler military jets while they are 12 miles away at a decibel reading of 10 decibels. Within 5 seconds, the jet would only be 11 miles away and the sound would double to 20 decibels. 5 more seconds, the jet would only be 10 miles away and the sound would double again to 30 decibels.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 11

Table of Extreme Noise from Growler Jet Fly Over of Spotted Owls

Below is a graph of the above table.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 12

Human hearing begins to be permanently damaged at 80 decibels. Therefore since spotted owl hearing is 10 to 100 times more sensitive that human hearing, it is likely that spotted owl hearing is permanently damaged at 70 decibels or less. This damage would begin to occur 30 seconds after the owl first hears the jet approaching and 30 seconds before the jet is directly overhead. This damage would continue for 30 more seconds as the jet was leaving.

Therefore with every jet flyover the owls would be exposed to toxic noise for at least one minute – sixty times more than the one second claimed by the Navy. It is likely that even one single fly over by a Growler jet could cause permanent hearing damage in the spotted owls. If there are 120 flyovers per day, each owl would be subjected to 120 minutes per day of chronic toxic noise. Over five days per week, this would equate to 600 minutes or ten hours of toxic noise per week. Over 52 weeks in one year, this would equate to 520 hours of toxic noise per year. By this point, the entire owl population would be deaf – and go extinct shortly after that as they would no loner be able to hear well enough to hunt their prey.

Part 4... Laws and Studies on Spotted Owl Populations

The following is a brief chronology of efforts during the past 45 years to protect biodiversity. This history is important because it reveals that the transgressions of the US Forest Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Navy today in terms of ignoring scientific research in order to maximize short term profits by sacrificing the long term health of the environment are very similar to the transgressions of the US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Logging Industry in the 1980s. There is a disturbing pattern of government agencies ignoring federal laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act and thus requiring the public to go to court in order to enforce these federal laws. In the 1970s and 1980s, Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service rubber stamping of logging permits led to the destruction of over 90% of our Old Growth forests. Now, the Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service rubber stamping of reckless Navy plans risk destroying the last remaining ten percent of our Old Growth forests and the owls that live in them. Below is a brief history of how all of this happened.

In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). (42 US Code 4331). Through this Act, the federal government recognized "each generation's responsibility to act as a trustee of the environment for future generations." The Act mandates a coordination of all Federal plans, agencies, policies, actions, puts the protection of our environment as a Federal policy, to "assure for all Americans safe, healthful, productive and esthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings...without degradation, risk to health or safety, or other undesirable or unintended consequences."

NEPA requires public notice in affected communities (which was not done in this case) and public hearings in affected communities (which also has not been done).

NEPA also requires the use of the most recent and best available science (which was not done in the Navy Environmental Assessment).

NEPA also requires that the US Forest Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to conduct an independent and accurate assessment of the claims made by the Navy (which thus far has also not been done).

NEPA also requires the US Forest Service to consider cumulative impacts of the proposed project and how it relates to other past, present and future projects and potential uses of our national forests. Cumulative impacts include the effects of future State, local, or private actions that are reasonably certain to occur in the area considered in the proposed project. Potential impacts of the entire project must be fully analyzed and disclosed. Thus far, the Forest Service has mistakenly limited its inquiry to merely the mobile electronic transmitters on Forest Service roads and refused to consider the actual interaction between the mobile transmitters and the planes flying overhead and how the noise of the entire proposed operation might affect endangered species such as spotted owls and marbled murrelets.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 14

NEPA Questions:

Why did the Forest Service fail to give adequate notice in the most affected communities of Port Angeles, Port Townsend and Forks?

Why has the Forest Service refused to provide recorded public hearings to allow the public an opportunity to ask questions of Navy and Forest Service officials?

When will the Forest Service hold recorded public hearing?

Why has the Forest Service not conducted their own independent research?

Why has the Forest Service failed to insist that the Navy use the best available science and conduct additional research needed to provide the public with information essential to determine the impact this project will have on humans and on wildlife?”

Why has the Forest Service refused to consider the cumulative impacts of the proposed project including noise from Growler jets flying over critical habitat for spotted owls?

In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act (ESA). (16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) The Endangered Species Act established protection over and conservation of threatened and endangered species and the ecosystems upon which they depend. The intention of the ESA is to protect not only endangered species but also protect the genetic diversity of all life on earth – recognizing that human life is also dependent on maintaining the genetic diversity of our ecosystem. Endangered species are considered the “canaries in the coal mine” in that they are “indicator species” of the health of the particular ecosystems – such as Old Growth Forests – as well as the health of the entire environment. The primary purpose of the ESA is to provide “...a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved ...“ (ESA, Sec. 2(b)). The ESA mandated that formal “consultation” occurs between Federal agencies and the US Fish and Wildlife Service before any actions could begin that might potentially harm the species or its habitat (ESA, Section 7).

In the 1970s, high speed logging machines were introduced which greatly accelerated the destruction of old growth forests.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 15

In 1973, the spotted owl was listed on a preliminary list of threatened species by the US Fish and Wildlife Service due to the rapid destruction of their habitat.

In 1974, I (David Spring) graduated with a degree in Science Education from Washington State University and began teaching Environmental and Outdoor Education Courses at various colleges in Washington State. During my three thousand wilderness outings between 1974 and 2004, I had a front row seat in watching the destruction of the Old Growth forests in Washington State.

In 1976, Howard Postovit conducted the first survey of spotted owls in Washington State including a survey of spotted owls in the Olympic Mountains. 14 owls were located at 13 sites in the Olympic Mountains. All were found in Old Growth forests. (See Gutierrez 1985).

David Spring Public Comment, Page 16

In 1977, Eric Forsman and others surveyed areas in the Cascade and Coast Ranges, including extensive areas of second-growth forests 40-90 years old. Spotted Owls were 12 times more abundant in old growth forests than in forests that were less than 80 years old. Later several more researchers confirmed the owl preference for old growth forests and also noted that the owls greatly preferred habitat near streams (which is true of nearly all wildlife). (See Forsman. Eric D.; Meslow. E. Charles; Strub, Manic J. Spotted owl abundance in young versus old-growth forests, Oregon. The Wildlife Society Bulletin 5(2): 43-47; 1977).

Based on the above study, also in 1977, the Oregon Interagency Task Force developed the first habitat management plan for the spotted owls on public lands in Oregon. 300 acres were recommended per owl pair. (See Gutierrez 1985).

In 1978, Ken Dzinbal conducted the second owl survey in Olympic National Park. Covering much more ground than the previous survey, he found 54 owls at 38 locations in 276 hours. (See Gutierrez 1985).

In 1980, the Oregon Washington Interagency Committee raised the recommendation for owl pair habitat be raised from 300 acres to 1000 acres per owl pair. This was based on a 1980 study by Forsman who tracked 6 owls pairs and found that they used a minimum of 1,008 acres to forage for food during a single year. The recommendation ignored the fact that five of the six owl pairs required more than 2000 acres of old growth forest. The average range size was nearly 3000 acres. This data and other similar studies were later submitted to the federal court as evidence that the Forest Service was not making a good faith effort to protect spotted owls.

In 1981, Olympic National Forest was directed to manage Northern Spotted Owl habitat using Spotted Owl Management Areas (SOMAS). The third survey was conducted by Maureen Beckstead. She found 41 owls in 332 hours. This was substantially fewer owls than had been found three years earlier. Many previously occupied sites were empty.

In 1982, the fourth survey was conducted by Maureen Beckstead. She found 40 owls in 442 hours of calling. In 1983, the fifth survey was conducted by Maureen Beckstead with the help of volunteers. The team spent 1577 hours calling and got 77 total responses and sightings. All of the above surveys were done on US Forest Service land on the Olympic Peninsula. In 1984, an estimate of the spotted owl population in Olympic National Park were made at 42 to 109 pairs.

In 1983, Parry et al published a controversial study concluding that the recent acceleration of logging of Northwest Old Growth forests (due to the new logging machines) was not sustainable over time. (See Parry B. T. Vuax H.J. and Dennis, N. 1983 Changing Concepts of Sustained Yield Policy on the National Forests Journal of Forestry 81:150 to 154).

In 1984, I (David Spring) began teaching Environmental Education and Outdoor Education course at Bellevue College in Bellevue Washington.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 17

Also in 1984, Eric Forsman published the first detailed study of the decline of the spotted owl population in NW Old Growth forests. In 1986, a version of this study was published by the National Audubon Society. This report was a key motivator for the Audubon Society to eventually file a lawsuit against the Forest Service. (See Forsman, Eric C. Meslow, and H.M. Wight. 1984. Distribution and biology of the spotted owl in Oregon. Wildlife Monographs 87:1-64 and Forsman, Eric and E C Meslow 1986 The spotted owl Page 742 to 761 in Audubon Wildlife Report National Audubon Society).

In 1985, Gutierrez et al published a landmark history of the research on spotted owls from 1974 to 1984. This report summarized the research of the preceding 10 years and concludes that at least 1000 pairs of spotted owls (2000 total spotted owls) would be required to maintain the species over time. It estimated the owl population as being:

“The present (1985) populations of spotted owls are about 1,200 pairs in Oregon (Carleson and Haight 1985), 1,000 pairs in Washington (U. S. Department of the Interior 1982), and 1,260 pairs in California (Gould 1985). These populations will probably decrease with continued harvesting of mature and old-growth timber (Forsman and others 1982).” Of the 1000 owl pairs in Washington in 1985, about one third were believed to be on the Olympic Peninsula. (See Gutiérrez, R. J., and Carey, A. B., tech. eds. 1985. Ecology and management of the spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest. General Technical Report, PNW-185. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, OR. 119 pp.

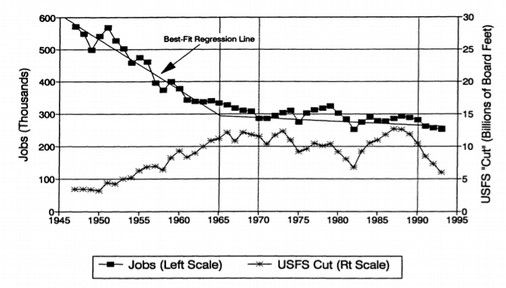

What really caused the loss of jobs in the logging industry?

Throughout the spotted owl litigation from 1987 to the present day, the owners of logging companies blamed the spotted owls for the loss of logging jobs. But the truth was that 90% of all logging job losses occurred 20 years before the first actions were taken to protect the last remaining stands of Old Growth forests. As the following chart shows, what caused the decline in logging jobs was not spotted owls, but greedy corporations who replaced their workers with machines to increase corporate profits.

Source: Freudenburg, William R.; Lisa J. Wilson; Daniel O'Leary (1998). "Forty Years of Spotted Owls? A Longitudinal Analysis of Logging-Industry Job Losses". Sociological Perspectives 41 (#1): pp. 1–2

David Spring Public Comment, Page 18

In the late 1980s, this widespread destruction of forests led leaders of the environmental movement in Washington State to sue the Forest Service for failing to maintain sustainable forest practices. Spotted owls were used as an indicator species of the health and viability of the Old Growth forest. These law suits were called Seattle Audubon I, Seattle Audubon II and Seattle Audubon III – although in every case there were numerous environmental organizations filing jointly. The filers included:

Seattle Audubon Society; Pilchuck Audubon Society; Washington Environmental Council; Washington Native Plants Society; Oregon Natural Resources Council; Portland Audubon Society; Lane County Audubon Society; Siuslaw Task Force, Plaintiffs versus. F. Dale Robertson, in His Official Capacity as Chief, United States Forest Service; United States Forest Service, an Agency of the United States, Defendants- 914 F.2d 1311 (9th Cir. 1990). The litigation was rapid and complex. But it is worth recounting here because it illustrates that justice can eventually prevail.

In October 1987, the Portland Audubon Society and other environmental organizations filed an action in federal district court for declaratory and injunctive relief, challenging forest management activities of the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of the Interior, as violating the National Environmental Protection Act ("NEPA"), 42 U.S.C. Secs. 4321-4347, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, 43 U.S.C. Secs. 1701-1782. The Portland district court dismissed the action and the Portland Audubon Society appealed the decision. In 1989, the federal court of appeals reversed the decision. (See Portland Audubon Society v. Hodel, 866 F.2d 302 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 109 S.Ct. 3229, 106 L.Ed.2d 577 (1989)). On remand, the district court again dismissed the action. The Portland Audubon Society again appealed the decision. The federal court of appeals again reversed the district court. On October 23, 1989, the Portland Audubon renewed its motion in the district court for summary judgment under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act. The case was eventually consolidated with the Seattle Audubon Society case on appeal.

In 1988, the US Forest Service created a new forest plan which it claimed would protect spotted owls from extinction. But the new plan was a farce as it ignored the best available science and continued massive logging of old growth forests.

On February 8 1989, the Seattle Audubon Society and other environmental organizations filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in federal district court in Seattle against certain US Forest Service administrative decisions arguing that the Forest Service 1988 plan did not provide adequate protection for Spotted Owls and their habitat. They moved for a preliminary injunction based upon the urgency of the matter. Federal district court judge William Dywer first rejected the preliminary injunction but later granted a renewed motion for preliminary injunction halting certain planned timber sales. (See 1989 William Dwyer Seattle Audubon Society et al, versus Robertson US District Court, Seattle Washington Civil Case C89-160).

In September 1989, Congress passed the Section 318 rider which went into effect October 23 1989. This bill allowed certain timber sales on certain old growth forests. The 318 rider stated: “The guidelines adopted by subsections (b)(3) and (b)(5) of this section shall not be subject to judicial review by any court of the United States.”

David Spring Public Comment, Page 19

On November 6, 1989, based on section 318, the district court in Seattle Audubon vacated the preliminary injunction. The district court rejected Seattle Audubon's argument that section 318 violates the separation of powers doctrine and is therefore unconstitutional. The district court retained jurisdiction over the case and certified for appeal under 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1292(b) its decision to vacate the preliminary injunction.

On December 21, 1989, the district court in Portland Audubon granted the government's motion to dismiss, based on section 318, over Portland Audubon's constitutional challenge to section 318. Both cases then went to the court of appeals.

On September 18 1990, the federal court of appeals responded with a ruling that the Section 318 act of Congress limiting judicial review was unconstitutional. (See Seattle Audubon Soc'y v. Robertson, 914 F.2d 1311 (9th Cir. 1990), cert. granted, 111 S. Ct. 2886 (1991). The Court of Appeals stated: “The Supreme Court "consistently has given voice to, and has reaffirmed, the central judgment of the Framers of the Constitution that, within our political scheme, the separation of governmental powers into three coordinate Branches is essential to the preservation of liberty... In this case we must decide whether, in enacting section 318, Congress went beyond the limits of its power established in the Constitution... By section 318, Congress for the first time endeavors to instruct federal courts to reach a particular result in pending cases identified by caption and file number... (This act) raises serious constitutional concerns in light of Article III's stated premise that the judicial power of the United States, encompassing cases and controversies, lies in the federal courts and not in Congress... Congress cannot "prescribe a rule for a decision of a cause in a certain way" where "no new circumstances have been created by legislation." 'We conclude that subsection (b)(6)(A) runs afoul of the separation of powers doctrine. Section 318 does not, by its plain language, repeal or amend the environmental laws underlying this litigation... Congress did not amend or repeal laws, as it unquestionably could do, but rather prescribed a rule for the decision of a cause in a particular way, without changing the underlying laws, as it unquestionably cannot do. Although the legislative history of section 318 disguises the act as changing legal standards, the statutory language itself does not do so. The first sentence of subsection (b)(6)(A) violates the separation of powers doctrine. The judgments of the district courts are REVERSED.”

On June 22 1990, the US Fish and Wildlife Service declared spotted owls as a threatened species. After this action, the Forest Service strangely claimed that they no longer had a duty to protect the owls because the duty had been transferred to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The federal court rejected this strange argument. But it shows how far the Forest Service was willing to go in order to continue its illegal logging practices. It was even willing to violate its own written regulations. The Forest Service's regulations, specifically 36 C.F.R. § 219.19, expressly require the planning process under the NFMA to identify habitat "critical for threatened and endangered species" and to determine objectives for such species "that shall provide for, where possible, their removal from listing as threatened and endangered species through appropriate conservation measures." Moreover, Section 219.27 provides that the "minimum specific management requirements" shall include measures for preventing the destruction or adverse modifications of critical habitat for threatened and endangered species.

See 16 U.S.C. §§ 1600-1687 (1985) ("NFMA"); 36 C.F.R. § 219.19.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 20

In October 1990, the Seattle Audubon Society filed an amended complaint challenging the new position of the Forest Service and insisting that the Forest Service had to comply with the Endangered Species Act as well as its own regulations. The Seattle Audubon Society asked for an injunction against all timber sales in spotted owl habitat pending preparation of such regional guidelines, as well as an accompanying environmental impact statement.

On March 7, 1991, US District Judge William Dwyer ruled in favor of the Seattle Audubon Society on cross-motions for summary judgment, holding that the Forest Service must comply with both the NFMA and the ESA before taking any action that will affect the owls. Testifying at a hearing in this case, biologist Eric Forsman stated, "There was a considerable amount of political pressure to create a plan which had a very low probability of success and which had a minimum impact on timber harvest."

On May 23 1991, US District Judge William Dwyer issued an injunction against the Forest Service disallowing timber sales in spotted owl habitat and halting all logging of Old Growth forests. (See Dwyer, W.L. 1991. Order on motions for summary judgment and for dismissal. Seattle Audubon Society et al., plaintiffs, v. F. Dale Robertson et al., defendants. No. 89099 (t)WD. Seattle, WA: U.S. District Court, Western District of Washington. 28 p. ) (771 F.2d 1081 (1991)). http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/771/1081/1657110/

It is worth reading Judge Dwyer's opinion because the disregard for federal law then appears to be re-occurring today. Here are quotes from Judge Dwyer's opinion:

“The records of this case and of No. C88-573Z show a remarkable series of violations of the environmental laws... In seeking a stay of proceedings in this court in 1989 the Forest Service announced its intent to adopt temporary guidelines within thirty days. It did not do that within thirty days, or ever. When directed by Congress to have a revised ROD in place by September 30, 1990, the Forest Service did not even attempt to comply. The FWS, in the meantime, acted contrary to law in refusing to list the spotted owl as endangered or threatened. After it finally listed the species as "threatened" following Judge Zilly's order, the FWS again violated the ESA by failing to designate critical habitat as required... More is involved here than a simple failure by an agency to comply with its governing statute. The most recent violation of NFMA exemplifies a deliberate and systematic refusal by the Forest Service and the FWS to comply with the laws protecting wildlife.”

“Further delays of this magnitude are neither necessary nor tolerable... Old growth forests are lost for generations. No amount of money can replace the environmental loss.”

Dr. Gordon Orians, an expert in avian populations and ecology, has testified:

Q. Can you summarize why you recommend that there be no further logging while the agency determines its new management plan?

A. I recommend a cessation of logging of owl habitat in the short run because I think the risk that the population crosses a very significant viability threshold is increased significantly by continued loss of its habitat. This will reduce the options to maintain viability in the future. (There is a)... very significant risks to the spotted owl population; that is, a reasonably high probability that it would cross such a threshold line.

THE PUBLIC INTEREST AND THE BALANCE OF EQUITIES

The court must weigh and consider the public interest in deciding whether to issue an injunction in an environmental case... It must also consider the balance of equities among the parties... The problem here has not been any shortcoming in the laws, but simply a refusal of administrative agencies to comply with them. This invokes a public interest of the highest order: the interest in having government officials act in accordance with law. See Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 485, 48 S.Ct. 564, 575, 72 L.Ed. 944 (1928) (Brandeis, J., dissenting).

The public also "has a manifest interest in the preservation of old growth trees... This is not the usual situation in which the court reviews an administrative decision and, in doing so, gives deference to agency expertise. The Forest Service here has not taken the necessary steps to make a decision in the first place yet it seeks to take action with major environmental impact... would constitute irreparable harm, and would risk pushing the species beyond a threshold from which it could not recover.”

Judge Dwyer ordered the Forest Service to prepare a new Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) that complied with the guidelines of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and to legally adopt a conservation management plan that complied with the guidelines of the Endangered Species Act by providing adequate protection for the Northern Spotted Owls by March 5 1992. The Forest Service immediately appealed Judge Dwyer's decision continuing to argue that it no longer had any duty to maintain a viable population of spotted owls once they were listed under the Endangered Species Act.

On December 23 1991, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Judge Dwyer’s ruling against the Forest Service. (See 952 F. 2d 297 - Seattle Audubon Society v. Evans, Appeal Nos. 91-35528 et al. (9th Cir. December 23, 1991)

http://openjurist.org/952/f2d/297/seattle-audubon-society-v-l-evans-us-seattle-audubon-society

This landmark appeal was argued by Michael Axline of the Western Environmental Law Clinic with the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon and Victor Sher, of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund in Seattle, Washington on behalf of the Seattle Audubon Society, the Portland Audubon Society and many others.

In its appeal, the Forest Service claimed that it was no longer required under the NFMA to plan for the future survival of the spotted owl because the Fish and Wildlife Service had declared the owl threatened under the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531-1543 (1985) ("ESA"). The Forest Service contended that it was only required to plan for "viable" species, and that once a species was declared threatened or endangered under the ESA, the species was no longer viable.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 22

The Federal Appeals Court held that the U.S. Forest Service was required to ensure the viability of the northern spotted owl and that the district court properly ordered an environmental impact statement in fashioning a remedy and determining appropriate time periods. Significant the present Navy application, the federal court of appeals noted that the Forest Service is required to “identify habitats critical to threatened or endangered species and prescribe measures to prevent their adverse modification. Id. § 219.19(a)(7).”

The federal Court of Appeals concluded: “The ESA list is not a list of animals to be written off. It is a mandate for all agencies involved to take aggressive steps to avoid a species' extinction and preserve its viability... The Forest Service's systematic refusal to follow the law in the past, as chronicled by the district court, is not an excuse for its avoiding the concurrent requirements of the NFMA and ESA in the future.”

Taking versus Harming

Under the Endangered Species Act enacted in 1973, the word "take" is defined in a broader way to include "harass," and "harm," 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). The broadest term, "harm," is defined by ESA to include habitat modification or degradation. "Harm" under the Endangered Species Act definition of "take" means: [A]n act which actually kills or injures wildlife. Such act may include significant habitat modification or degradation where it actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering. The Appeal Court's affirmation of the district court's opinion basically created a stalemate that led to a dramatic reduction in logging in the Pacific Northwest – but no acceptable plan for protecting spotted owls.

In October, 1992, presidential candidate Bill Clinton promised that, if elected, he would convene a “forest summit” to address the issue. The Presidential election and subsequent changes in the Administration quickly led to new interest in resolving the timber and forest management conflict in the Northwest.

In November 1992, Bill Clinton was elected President in part on a pledge that he would solve the spotted owl controversy.

In April 1993, shortly after taking office, President Clinton ordered all sides in the spotted owl controversy to meet in Portland Oregon and stay there until an agreement had been worked out. Together, these groups which included environmentalists, logging corporations and the US Forest Service negotiated a compromise called the Northwest Forest Plan that was supposed to provide protected habitat for spotted owls by eliminating logging on most Old Growth Forests. The plan used a concept developed by Edward O. Wilson called Clusters and Corridors where by spotted owls would have home communities and could migrate between home communities to avoid genetic isolation and preserve genetic diversity. The single most important cluster was the spotted owl population on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains in and near Olympic National Park. The team assembled to hammer out the details of this plan was called the Forest Ecosystem Management Assessment Team (FEMAT) and consisted of Federal, State, private, and university specialists in many fields including ecology, biology, economics, sociology, forestry, ecology, and many other areas. Over 600 persons were ultimately involved.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 23

On 13 April 1994, the Secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture adopted the FEMAT plan as the 1994 Record of Decision (1994 ROD See USDA and USDI 1994).

The Record of Decision amended the planning documents of two Forest Service regions, 19 National Forests, and 7 BLM districts. It called for conservation of much of the northern spotted owl habitat on Forest Service and BLM lands, which hold 90 percent of the Federal land area within the range of the northern spotted owl (Dwyer 1994). Of this Federal land area, 77 percent would now occur as various reserves,

On December 21 1994, Judge Dwyer formally approved what was now called the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan. Judge Dwyer reinforced the importance of monitoring in his decision declaring the Plan legally acceptable: “Monitoring is central to the [Northwest Forest Plan’s] validity. If it is not funded, or done for any reason, the plan will have to be reconsidered.” (See Dwyer, W.L. 1994. Seattle Audubon Society, et al. v. James Lyons, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, et al. Order on motions for Summary Judgment RE 1994 Forest Plan. Seattle, WA: U.S. District Court, Western District of Washington).

In November 1994, just before the new Forest Service Plan was approved by Judge Dwyer, I wrote a book about the Old Growth Forests and the need to protect endangered species. This book as available for free download at the following link:

http://davidspring.org/2-uncategorised/4-snowbirds-a-story-of-hope

In 1996, a comprehensive analysis of the rate of change of the spotted owl population was published. Called a “meta-analysis,” the study was conducted by Burnham and others that merged the demographic studies of individual northern spotted owl populations. This was done to determine the overall trend of the spotted owls throughout all geographic study areas combined. Results indicated that the overall spotted owl population was declining at a rate of 4.4 percent.

1996 King County Snoqualmie River Middle Fork Planning Commission and Washington State Department of Natural Resources Habitat Conservation Plan

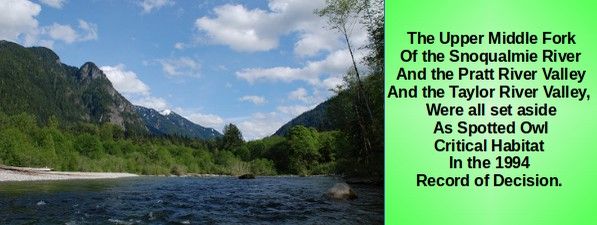

One of the requirements of the 1994 Record of Decision was that a series of “clusters” be established in Washington State to act as home bases for spotted owls. These are primarily located at relatively low elevation forests in National Parks and wilderness areas. However, it was known that the distance between the cluster at Mount Rainier National Park and the cluster in the Glacier Peak Wilderness area were too far apart – and the Alpine Lakes Wilderness area near Snoqualmie Pass was too high in elevation to provide suitable habitat for spotted owls. It was therefore wisely decided by all parties to turn the Upper Middle Fork Valley east of North Bend Washington into a semi-wilderness area. This would require cooperation from the US Forest Service and the Washington State DNR which managed the Mount Si Conservation area - thousands of acres of wildlife habitat near North Bend. A King County Commission, called the Middle Fork Planning Commission was formed to plan the future of this new wilderness area.

Coincidentally, my home (which has an Old Growth forest on a portion of it) was located in the middle of this conservation area. I was therefore appointed to this King County Commission and helped write the plan to preserve the Old Growth forests in the Upper Snoqualmie River Valley.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 24

During this time, I became more aware of the DNR plans to save (or destroy) the spotted owl population in Washington State. My home is not far from where this picture was taken.

In 1996, while I was serving on the Middle Fork Commission, as a part of the negotiated settlement to resume logging on Washington State DNR lands, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources produced 2 documents totally more than 1,000 pages describing their proposed Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). This plan was supposed to be similar to and supplement the federal forest plan. Instead, as I read the plan, it became obvious that the Washington State DNR was attempting to carry on its “logging as usual” by grossly distorting the scientific literature on standards to protect spotted owls. The State HCP basically said “Let us log Old Growth Forests now and we promise we will provide the owls with suitable habitat 50 years from now.”

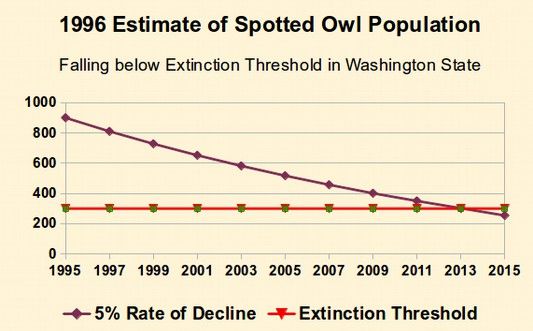

On May 18, 1996, I provided the US Fish and Wildlife officials who were reviewing the State HCP with a detailed 20 page analysis showing that if the State Plan was adopted – allowing them to kill hundreds of spotted owls – that there would not be any spotted owls left 50 years from now. The 20 page report is available for free download at the following link:

http://washingtonenvironmentalprotectioncoalition.org/david-spring-research-reports

I will briefly summarize the results here. At the time, there were only two official studies on spotted owl population rates of decline in Washington State. One somewhat biased study concluded the rate of decline was only one percent per year. The other better done study concluded the rate of decline was 12% per year. The State DNR plan used the more optimistic rate of 1 percent decline and ignored the other study completely. I argued that this violated the Endangered Species Act which called for using the “best available science.” I argued that, in the absence of other information, the weighted average of the two studies should be used. This would mean an assumed rate of decline of 5% per year. Shortly after I submitted this report, a detailed analysis by Burnham (1996) concluded that the rate of decline was 4.5 percent per year.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 25

Next I estimated the spotted owl population in Washington State based on the two most reliable sources available at that time. Here is a quote from my report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service: “The actual Spotted Owl population currently existing in Washington state is unknown. The U.S.F.W.S. stated (in their Draft E.A.A. for the 4(d) Rule, Page 69, 1995) that there are 762 known activity centers (pairs and singles) in Washington state. A survey of Washington state Wildlife biologists indicated an estimate of about 900 (or less) total owl pairs (including known and unknown owls) at the present time (1995). I therefore used an estimate of 900 spotted owl pairs in 1995 in Washington State.

I next used the theories of biologist E. O. Wilson to estimate the “extinction threshold” below which it would be very difficult to restore spotted owls to a viable population. The details of this analysis are provided in my report. My conclusion was that the extinction threshold is about 300 pairs of Spotted Owls for the entire State. I then provided a table of the decline in spotted owl populations based upon six different sets of assumptions. Below is a graph showing the rate of decline for what I described as the most likely scenario which was a rate of decline of 5% per year.

As you can see from the above graph, I predicted in 1996 that if the rate of decline was 5%, then the spotted owls in Washington State would pass the Extinction Threshold of 300 pairs in about 2014. Sadly, the US Fish and Wildlife Service ignored my study. However, it was widely shared in the environmental community. In 2003, the Northwest Ecosystem Alliance was conducting a review of the Washington State DNR Habitat Conservation Plan. They contacted me and asked me to update my study. By this point, there had been an additional study on the rate of decline of spotted owl populations in Washington State. This study, done by Eric Forsman, found that the rate of decline was about 6% - with the rate of decline in the Olympic Mountains being about 4%.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 26

On the request of the Northwest Ecosystem Alliance, on June 18 2003, I sent a followup study to the US Fish and Wildlife Service which was nearly identical to the report I sent them in 1996. This report is available at the following link:

http://washingtonenvironmentalprotectioncoalition.org/david-spring-research-reports

Essentially, my conclusion was that spotted owls in most parts of Washington State would pass the Extinction Threshold shortly bat about 2014 and that spotted owls in the Olympic Mountains would pass the extinction threshold in about 2015 to 2016.

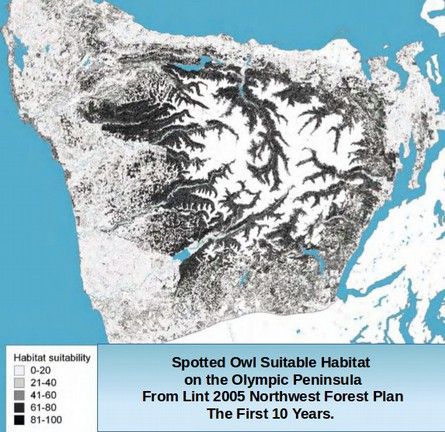

In September 2005, Lint published a review of the research on spotted owl populations during the preceding 10 years. (See Lint, J., 2005. Northwest Forest Plan--the first 10 years (1994-2003): status and trends of northern spotted owl population and habitat. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-648. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 176 p.

http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/publications/pnw_gtr648/).

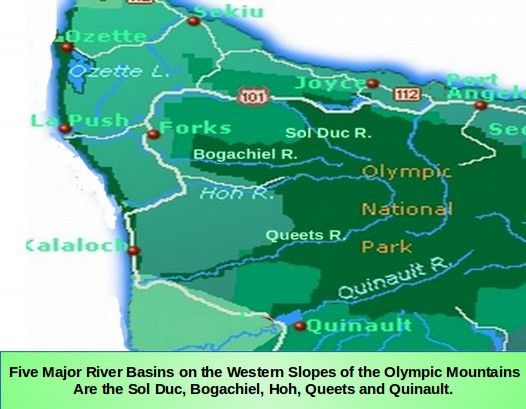

Below is a map that was produced by Lint of the best habitat for spotted owls on the Olympic Peninsula.

You can see that the best habitat for spotted owls remaining in the Olympic Peninsula is right in the middle of the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains. This is exactly where the Navy now wants to conduct their electronic warfare games.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 27

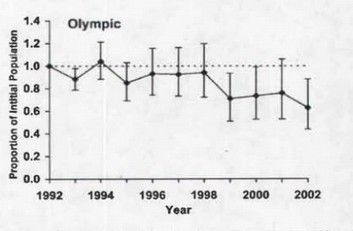

In July 2006, Anthony et al published a summary of spotted owl population research based upon work completed in 2004. The conclusion of this team was that the rate of decline of spotted owls in the Olympic Mountains was 4.4 percent – similar to my 1996 and 2003 conclusions and similar to other research on the topic. The study also concluded that about one third of the spotted owls in Washington State were in the Olympic Mountains. This study found 395 adults in the Olympics by 2003 for about 200 adult pairs. Below is a chart of the rate of decline of spotted owls from Anthony page 26 Figure 9:

See Anthony RG, Forsman ED, Franklin AB, Anderson DR, Burnham KP, White GC, Schwarz CJ, Nichols JD, Hines JE, Olson GS, Ackers SH, Andrews LS, Biswell BL, Carlson PC, Diller LV, Dugger KM, Fehring KE, Fleming TL, Gerhardt RP, Gremel SA, Gutierrez RJ, Happe PJ, Herter DR, Higley JM, Horn RB, Irwin LL, Loschl PJ, Reid JA, Sovern SG (2006) Status and trends in demography of northern spotted owls, 1985-2003. Wildl Monogr 163: 1-47.

http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/journals/pnw_2006_anthony001.pdf

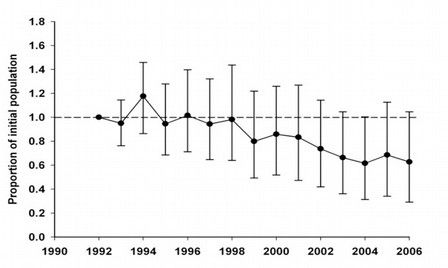

In 2011, Dr. Eric Forsman published a book with the following chart summarizing his research on the decline in the spotted owl population in Washington State:

David Spring Public Comment, Page 28

Source: Dr. Eric Forsman excerpted from the manuscript “POPULATION DEMOGRAPHY OF NORTHERN SPOTTED OWLS” in press at the California University Press. http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/olympia/wet/team-research/owl-res/index.shtml © 2011 OPB

Elsewhere in his book, Forsman essentially agreed with my 1996 analysis that there were about 900 spotted owl pairs in Washington State in 1994. The reason the above chart is stable to 1998 is simply because there were no studies during that period. The reason for the huge brackets around the dots is because with so few studies, there is a high degree of statistical uncertainty as to what the spotted owl population really is in Washington State. However, his research concluded that the population of spotted owls declined in half between 1994 to 2006 – which is almost precisely what I predicted would happen in my 1996 study.

Between 2005 ro 2007, despite all of the above research confirming the decline in spotted owl population, the Bush administration attempted to increase logging on Old Growth Forests. There have been numerous lawsuits on all sides in the past few years as private corporations seek to get the last drop of profit out of the timber in these Old Growth forests. Even after Obama was elected in 2008, the lawsuits and the logging have continued.

The conclusion of all of the above research is that the spotted owl population is currently on the brink of passing the Extinction Threshold in Washington State. In the Olympic Mountains, unless there are radical changes in the actions of the Washington State DNR and the US Forest Service, spotted owls will pass the Extinction Threshold in the Olympic Mountains sometime between 2015 to 2017.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 29

Part 5... Evidence Spotted Owls are Very Near the Extinction Threshold Cliff

We will next estimate the current population of spotted owls currently hanging on to existence on the Western slopes of the Olympic Mountains as this is extremely relevant to the need to protect owls and their habitat from any further degradation.

We have previously shown that in 1994, in agreement with Forsman, there were about 900 pairs of spotted owls in Washington State in the early 1990s. Since about one third of the remaining Old Growth Forest in Washington State is on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains, we can assume that about one third of these 900 pairs of spotted owls – or 300 pairs of spotted owls – lived on the west slopes of the Olympic Mountains in 1994. Forsman and others have concluded that the rate of decline of the spotted owl population in the Olympic Mountains is 4% - or less than in the rest of the State of Washington where the rate of decline was from 5% to 7%.

In the previous section, I used theories from E. O. Wilson to estimate that the Extinction Threshold in Washington State was 300 pairs of spotted owls. This means thatthe Extinction Threshold in the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains would be 100 pairs of spotted owls. This would mean 20 or fewer pairs of spotted owls at each of the western Olympic Mountains five great rivers: the Sol Duc, the Bogachiel, the Hoh, the Queets and the Quinault.

Sadly, all five of these major rivers and all five remaining populations of spotted

owls are being targeted for as part of the Navy's proposed war zone.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 30

In 1994, there were about 300 pairs of spotted owls in these five major river basins. This would mean about 60 pairs of spotted owls in each of the five major basins. At a 4% rate of decline determined by Forsman and others, this would mean a loss of 12 owl pairs out of the original 300 owl pairs per year or 24 owl pairs every 2 years. Below is a graph of how long it would take the spotted owls at this rate to reach the extinction threshold of 100 owl pairs.

Thus, even without the Navy War Zone, the spotted owls in the western Olympic Mountains are hanging on by a thread. Without major changes by the US Forest Service and/or the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, the spotted owls in the western Olympic Mountains will pass the extinction threshold somewhere around the year 2020. Even today, in 2014, there are only about 116 spotted owls left in the western Olympic Mountains. It will only take the loss of 16 more owls to push the owls over the extinction threshold cliff.

Part 6... Understanding the Extremely Quiet World of Spotted Owls

Earlier in this public comment, we reviewed the concept of decibels and showed that spotted owls evolved to live in a world that is much quieter than the human world. Here we will take a more detailed look at the extremely quiet world of spotted owls. Owls have evolved many important adaptations which help them hunt in the extremely quiet world of an Old Growth Forest. These include large heads, accommodating large eyes and ears, extremely mobile heads, capable of rotating 270 degrees to point their ears in the sound of their prey, asymmetrical ears, able to calculate flight angles of prey and feathers that absorb all sound, creating silent flight. All of these adaptations are intended for success in a quiet environment!

David Spring Public Comment, Page 31

Comparing the Extreme Quiet of the Hoh Rain Forest to a Normal Conversation

Humans live in an extremely noisy world compared to the extremely quiet world of spotted owls. Our ears have gotten used to this noise and even manage to screen much of it out. In addition, if the noise level in our world gets too loud, we can cover our ears with our hands or put on commercial grade ear mufflers. The spotted owls do not have hands and do not have access to ear mufflers. The average sound level in an Old Growth forest is 20 decibels. To a spotted owl, even a human whisper, which is 30 decibels, would sound loud. The Hoh Rain Forest has been measured as 10 decibels – one of the quietest places on earth. Below is a graph comparing the sound in the Hoh Rain Forest to a normal human conversation.

In the extremely quiet world of spotted owls, even a human whisper is loud. With their ears adjusted for such a quiet world, a normal human conversation sounds to spotted owls much like a jet aircraft sounds to us. This is why the US Fish and Wildlife Service advises field monitors to be extremely quiet while doing field surveys of spotted owls.

2006 US Fish and Wildlife Service Report on the Importance of Quiet for Birds

“Birds more than most any vertebrate group other than primates, make use of a rich array of sounds for communicating, finding mates, expressing territorial occupation, and numerous other social behaviors. But hearing is also more than this. Birds, as other animals, also use hearing to learn about their overall environments – in effect, they use sound to sample what Bregman (1991) called the “acoustic scene.” This acoustic scene is the array of sounds in the environment which may arise from biological or non-biological sources such as predators moving through the environment or the wind moving through trees. This acoustic scene covers an area all around an animal, and it is just as rich at night as it is in daylight. In effect, the acoustic scene enables an animal to “see” beyond its eyes and learn a great deal about its extended environment. From the perspective of this Report, we must consider that both environmental and communication sounds are important in the lives of birds. Thus, while we tend to think in terms of effects of human-generated sounds on communication, it must be kept in mind that the use of sound by birds extends beyond sounds used for communication to the much larger acoustic scene. Such sounds enable birds to be aware of their whole (acoustic) environment. When noise interferes with a bird sampling the environment and learning the relationship among sound sources and the environment, the individual, and perhaps the species, is at risk.”

David Spring Public Comment, Page 32

An Important Characteristic of Old Growth Forests is that they are very quiet

The Sound Level in the Western Slopes of the Olympics has been rated as the quietest in the United States. A location in the Hoh River valley was identified as the quietest place in the lower 48 (seehttp://onesquareinch.org/). This unique aspect of the Olympic Mountains is one of the reasons tourists come to visit it. They come for the silence. In fact, one center that treats veterans for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is located on the western slopes of the Olympic Mountains precisely because of this quietness and the therapeutic value it has on soldier recovery. According to Richard A. Jahnke, President of the Admiralty Audubon Society: “Portable diesel generators required for the mobile emitters and frequent overflights by fighter jets - audible for many miles in all directions - will certainly degrade the soundscape of this location and make it less desirable for tourists - a hardship for an already economically challenged region.”

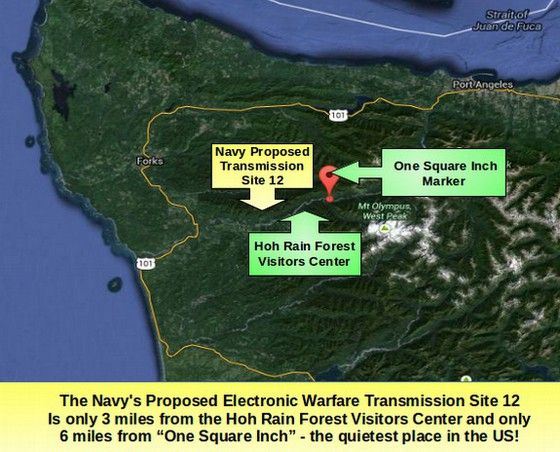

The “One Square Inch” marker, located 3 miles east of the Hoh Rain Forest Visitors Center, and in the middle of one of the most ancient forests in the world is considered the quietest place in the United States by sound researcher Gordon Hempton - with a decibel rating of 10 decibels. A normal Old Growth forest is 20 decibels and a human whisper is 30 decibels. The Navy proposes to locate Electronic Warfare Transmission Site 12 only 3 miles west of the Hoh Rain Forest Visitors Center and then attack Site 12 thousands of times with hundreds of Growler Military Jets which have a decibel rating as high as 150 decibels.

David Spring Public Comment, Page 33

One Square Inch of Silence

Here are links to a couple of 3 minute YouTube videos about the One Square Inch project. Sound researcher, Gordon Hempton, explains the importance of one square inch of silence. Also visit http://onesquareinch.org/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0xHfFC_6n0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFaHf4HQr2M

The US Fish and Wildlife Service surveying protocol specifically warns against excessive noise as being harmful to spotted owls:

“PROTOCOL FOR SURVEYING PROPOSED MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES THAT MAY IMPACT NORTHERN SPOTTED OWLS Endorsed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service , February 2, 2011 , Revised January 9, 2012

This protocol should also be applied to activities that disrupt essential breeding activities and to activities that may injure or otherwise harm spotted owl other than through habitat modification (e.g., noise disturbance, smoke from prescribed fire)... Do not broadcast loudly and do not use agitated or barking calls near a potentially active nest – this could agitate the female more than necessary or draw females off the nest.

10.3 If Spotted Owls Are Detected in the Spot Check Area: If spotted owls are detected in the spot check area, ALL ongoing operations that have a likelihood of direct harm to a spotted owl and/or creating above-ambient noise shall be postponed. ”

http://www.fws.gov/oregonfwo/Species/Data/NorthernSpottedOwl/Documents/2012RevisedNSOprotocol.2.15.12.pdf

David Spring Public Comment, Page 34

On July 31, 2006, the Arcata Fish and Wildlife Service Office of the U. S. Fish and